Learning Modules

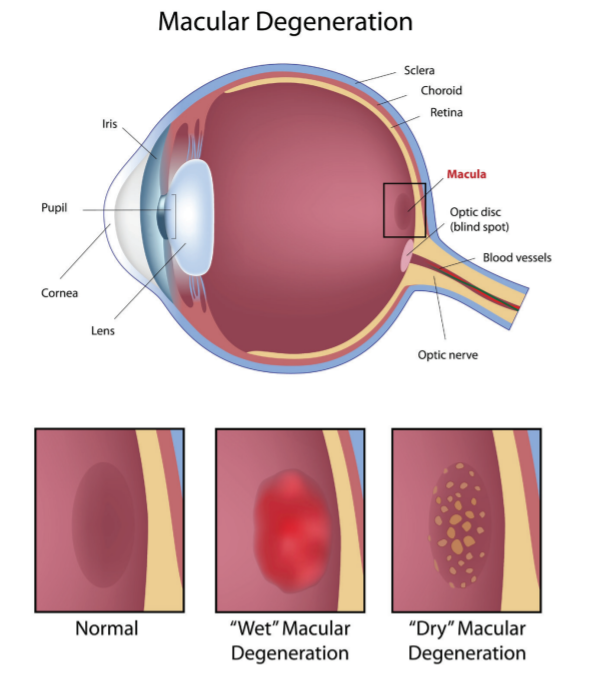

People with AMD have central blindness, but peripheral vision is spared. AMD is usually described as 2 forms:1-3 (See Figure below)

- “Dry” (atrophic) AMD: approximately 80% to 90% of cases are considered the dry form which can slowly progress to late- (geographic) or end-stage disease.

- “Wet” (neovascular, new vessels) AMD: approximately 10% to 20% of cases are considered the wet form which has a more rapid course that affects vision. Wet AMD is responsible for up to 90% of cases of legal blindness caused by AMD.

Although AMD has 2 forms, based on how it develops, it also can be separated into 3 stages based on signs and symptoms that are experienced:1

- Early (1) and intermediate (2) disease is dry AMD; early-stage AMD usually has no symptoms

- Advanced disease (3) has progressed to geographic or wet AMD

When visual changes occur, AMD is most likely intermediate to advanced disease. Early detection and referral to an ophthalmologist is important because treatment as soon as possible has more successful outcomes for wet AMD.1,5

The American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) recommends the following for comprehensive eye exams in adults with no risk factors for AMD or signs of disease:1,3,6

- Under age 40 years: every 5 to 10 years

- Ages 40 to 54 years: every 2 to 4 years

- Ages 55 to 64 years: every 1 to 3 years

- Age 65 and older: every 1 to 2 years

You should have a comprehensive medical eye evaluation with an ophthalmologist at age 40 if you have not previously had one.1,3,6

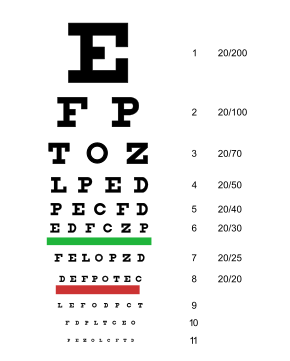

Occasionally people with loss of vision in one eye are not aware of any problems with their vision when sight in the other eye is still good;1,5 therefore, a Snellen exam by an eye care professional may reveal any vision changes that only affect 1 eye. (See Figure below)

People with symptoms or who have risk factors for AMD should have closer follow up by an eye care professional, and decisions on the number of visits should be made on an individual basis.1,3,6 Persons with significant risk factors should see an ophthalmologist.

People with symptoms of dry AMD complain of a slow blurring of vision in one or both eyes. Activities that require fine visual acuity such as driving or reading are hard to do. They may need to use brighter lights or possibly need to use a magnifying lens for specific tasks.1,7

People with wet AMD may complain of a quick onset of visual alteration or complete loss of central vision in one eye. AMD usually already exists in both eyes, but most frequently only presents in one. Straight lines will appear wavy and distorted, and the edges of windows or doors may appear curved.1,7

People may be given an Amsler grid to self-evaluate on a weekly basis for any changes in vision, such as missing areas of the grid or distorted/wavy lines.1 See the Figure below for an example of a patient self-evaluation of visual changes using an Amsler grid.

Everyone with AMD should be educated about healthy lifestyle choices including regular exercise; smoking cessation; wearing protective eyewear in the sun; and a diet that incorporates fruits, vegetables, fish, and nuts.1 Early recognition and coordinated care between primary care providers and vision specialists will lead to timely management, which may decrease the occurrence of permanent blindness due to AMD.1

Two studies sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Age-Related Eye Disease Study 1 and 2 (AREDS 1 and 2), have provided evidence which support that nutritional supplements can reduce the risk of AMD progressing to a more advanced state.1,8 These nutrients include:9

- Glutathione (GSH)/selenium and vitamin D3 status

- The family of vitamin E molecules known as tocotrienols/tocopherols

- Polyphenols

- The calcium/magnesium ratio

- Omega-3 fatty acids

- Zeaxanthin

- Activities that enhance endothelial nitric oxide production

Based on the results from AREDS 1 and 2, persons with intermediate AMD or advanced AMD, or vision loss in one eye due to AMD, are advised to take a combination of antioxidant supplements and zinc.1

- Nonsmokers and former smokers can follow the regimen outlined in AREDS 1: vitamin C, vitamin E, beta-carotene, and zinc.

- AREDS 2 replaced beta-carotene with lutein and zeaxanthin with similar risk reduction; smokers are advised to follow this regimen due to an increased risk of lung cancer with beta-carotene supplementation.

Lutein, zeaxanthin, and beta-carotene all belong to the same family of vitamins, and are abundant in green leafy vegetables.7 Glutathione stimulating hormone (GSH) is also found within the following dietary sources:9

- GSH: avocados, spinach, asparagus, watermelon, and walnuts; proteins such as chicken, chickpeas, and lentils

- Cysteine (sulfur bearing): turkey breast, eggs, sockeye salmon, yogurt, wheat germ, whey protein, garlic, onions, soy, red bell peppers, and broccoli

- Selenium: sardines, Brazil nuts, clams, oysters, turkey breast, and garlic

Nutritional supplements formulated based on these studies are available and their labels may refer to either AREDS or AREDS2.7

First-line therapy for persons with wet AMD is intravitreal injections with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors; these agents limit the destructive effects of neovascularization on retinal tissue and can stabilize or may possibly reverse vision loss.1,10 Photodynamic therapy is typically used when there is no response to treatment with VEGF inhibitors. It can be used alone or in combination with VEGF-inhibitor medications. With photodynamic therapy, a dye that is sensitive to light is injected with an activating laser applied through the eye. Tissues with new vessels hold more dye than other vessels which causes damage to these new vessels.1

References

- Cunningham J. Recognizing age-related macular degeneration in primary care. JAAPA. 2017;30(3):18-22.

- Cheung CM, Wong TY. Is age-related macular degeneration a manifestation of systemic disease? New prospects for early intervention and treatment. J Intern Med. 2014;276(2):140-153.

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Age-Related Macular Degeneration PPP—2019. https://www.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/age-related-macular-degeneration-ppp. Accessed April 3, 2020.

- American Optometry Association. Macular Degeneration Fact Sheet. https://www.aoa.org/Documents/MacularDegeneration_FactSheet_Web.pdf. Accessed April 7, 2020.

- Marra KV, Wagley S, Kuperwaser MC, et al. Care of older adults: role of primary care physicians in the treatment of cataracts and macular degeneration. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(2):369-377.

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Comprehensive Adult Medical Eye Evaluation—2015. https://www.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/comprehensive-adult-medical-eye-evaluation-2015. Accessed April 3, 2020.

- NIH/NEI. Age-related Macular Degeneration: What You Should Know. https://www.nei.nih.gov/sites/default/files/health-pdfs/WYSK_AMD_English_Sept2015_PRINT.pdf. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- Schmidl D, Garhöfer G, Schmetterer L. Nutritional supplements in age-related macular degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015; 93(2):105-121.

- Richer S, Ulanski L, Natalia A Popenko NA, et al. Age-related macular degeneration beyond the Age-related Eye Disease Study II. Adv Ophthalmol Optometry. 2016;1(1):335-369.

- Michalska-Malecka K, Kabiesz A, Nowak M, Spiewak D. Age related macular degeneration—challenge for future: pathogenesis and new perspectives for the treatment. Eur Geriatr Med. 2015;6(1):69-75.